Steven Morse personal website and research notes

Odds, Bets, and Probability

Written on January 20th, 2025 by Steven MorseThis post is a note-to-self on the nitty-gritty details of betting odds that you don’t often find written out explicitly (or at least not in the way I want). I am not a professional gambler, so if you’re looking for that kind of context with this information, see you later!

In this post, I’m just going to examine odds as a relationship between three terms: odds, payouts, and probabilities. We’ll look the various forms of odds (decimal odds, fractional odds, American odds), and how they map to each other and to probability. We’ll also look at how the house taking a cut muddles the otherwise clean relationship between these three values (odds, the payout, and the chances).

In the next post, I plan to look at how this plays out over time, with a bankroll, etc, and that will get us into random walks. After that, I’d like to write about betting strategies, like the Kelly criterion.

Odds vs. Probability

“Odds” and “probability” are the same thing expressed different ways, and in a gambling context, they are further connected, directly, to the potential net winnings on a bet.

In statistics, odds are defined as the ratio of the probability the event will happen to the probability it will not.

\[\text{odds} = \frac{p}{1-p}\]We might use odds instead of probability because it makes the math tidier — have a look at logistic regression, which uses the “log odds” (logarithm of the odds).

As an example, if an event will happen with \(p=0.75\), then its odds are “3” (or “3 to 1”, like 3/1=3) to happen because \(0.75/(1-0.75)=3\). We can work the other way too: let the fraction be “a to b”, and we have

\[\begin{align*} \frac{a}{b} &= \frac{p}{1-p} \\ a(1-p) &= bp \\ p &= \frac{a}{a+b} \end{align*}\]So if we see “3 to 2” odds, we can figure this as \(3/(3+2)=0.6\). Alternatively, notice \(p=\text{odds}/(1+\text{odds})\), so for “3 to 2” we have \(3/2=1.5\) and a probability of \(1.5/2.5=0.6\).

Go check out the Wikipedia page on odds, the whole intro is mostly doing the map between a phrase like “X to Y against” and a probability (i.e. a number between 0 and 1). But in each case, it’s a direct mapping: “3 to 2 against” maps to “40 percent” probability (aka 0.4), etc.

Odds and probability are different in that, very often, odds are connected to a bet and therefore some form of profit/loss.

Here’s how we can connect those ideas. Define \(w\) as the amount you win for a 1 dollar bet (that is, the amount you would win in addition to getting your dollar back), and let \(p\) be the probability of winning. Then the expected value (EV) of your bet is

\[E = p\ast w + (1-p)\ast (-1) = pw + p - 1\]So, if we want to have positive EV, we’d hope we are offered a bet such that \(pw+p-1>0\) or in other words \(w>(1-p)/p\). The breakpoint, when \(E=0\), gives

\[w = \frac{1-p}{p}\]For example, if an event is 50/50, the breakeven payout amount would be \(w=1\) (risk a dollar to make a dollar), meaning the bettor’s EV is 0. Any winnings higher than that is, in the long run, in the bettor’s favor (\(E>0\)), and vice versa.

So of course the guy offering this bet, the “bookmaker”, who has to potentially pay you the winnings, is going to pick this breakeven point. (If you’re thinking, what about the house cut! Just wait, we’ll get there.) It actually ensures his EV is zero also, because his EV is just the negative of yours:

\[E_{\text{book}} = p(-w) + (1-p)(1) = 0 \quad\Rightarrow\quad w = \frac{1-p}{p}\]So a bet defined this way, as \(w=(1-p)/p\) is called a “fair bet”.

This is connected back to the formal “odds” definition by noticing this fair bet \(b\) is

\[w = \frac{1-p}{p} = \frac{1}{\text{odds}}\]For example, if an event’s odds are “3 to 1” (aka 3), this implies probability \(p=0.75\), and so a bookie could offer the fair bet of 1 dollar stake gets winnings of \(w = 0.25 / 0.75 = 1 / 3 = 0.33\). Since the event has good odds of happening, you’re only offered 33 cents on a 1 dollar bet.

Again, “odds” and this fair bet aren’t necessarily linked (after all, you could have a bookie who likes giving money away!), but since they are effectively always aligned, they are very often in practice used almost interchangeably. Let’s look at some examples.

Different ways to say the same thing

Depending on what part of the world you’re in, “odds” are defined differently, but there is a straightforward one-to-one map between them all.

In this section, we will show the one-to-one map between all three odds flavors, their associated payout, and the implied probability. We will keep using this relationship:

\[w = \frac{1-p}{p} = \frac{1}{\text{odds}}\]In the next section, we will show that although the odds tell you the true payout, they do not necessarily tell you the true probability because the bookmaker has his hand on the scale.

Sidenote: to a boring, academic type, it may seem silly to have all these equivalent terms. It’s “+110 moneyline odds”, it’s “3 to 2”, it’s 1.5, … it’s all the same! But I reckon to an actual gambler, something like “+110” starts to acquire a feel to it that \(p=0.4\) doesn’t have.

We’ll look at three types of odds:

- Decimal odds (or “European” odds).

- Fractional odds (or “British” odds). Like “3:2” or “5:1”. Also common in horseracing.

- Moneyline odds (or “American” odds). Like “-110” or “+220” (these are the weirdest btw)

Decimal odds

Decimal odds represent the winnings and the stake. Specifically, for decimal odds \(D\), a 1 dollar bet wins \(D-1\) dollars. For example, a bet of one dollar on decimal odds of 2 earns you 2 dollars: your original dollar back, and one more.

Decimal odds corresponds directly to the probability of winning via \(1/D=p\), or \(D=1/p\), because recall your winnings on a fair bet is \(w=(1-p)/p=(1/p) - 1\), and since \(w=D-1\), we find \(D=1/p\).

Summary:

\[w=D-1, \qquad p=1/D\]Fractional odds

Fractional odds represent winnings, and are things like 3:2 or 5:1 (or “3/2”, “5/1”, or “3-2”, etc), which in the context of betting should be read like “3/2 against you”. Denote the numerator/denominator as \(a/b\), and we say for fractional odds, a bet of $1 wins you \(F=a/b\) dollars. Instead of representing it as a fraction, you can think of it as a decimal (e.g. 3:2 = 1.5). (This decimal version is sometimes called Hong Kong odds.)

We already connected fractional odds earlier to probability: for fractional odds \(F=a/b\), we know \(p=a/(a+b)\). And since in betting terms, odds of “3:2” really mean “3:2 against”, we know we need to flip the probability for our bet: the probability of win is \(p'=1-p\), which is \(p'=1-p=b/(a+b)\). Now connect this all back to our previous formulas with $$w=(1-p)/p=a/b$.

Summary:

\[w=F=\frac{a}{b}, \qquad p=\frac{b}{a+b}\]Moneyline odds

Weirdest ones. The first idea is to rebase everything to be off 100 bucks instead of 1, and then to keep that spirit up by having all the odds stay triple digits, regardless how low they go, by defining the odds differently low and high.

-

Positive moneyline odds represent winnings on a 100 dollar wager. For example, 3:1 (against) odds would have a moneyline of +300, or winnings of 300 on a 100 dollar bet.

-

Negative moneyline odds represent how much money must be wagered to win 100. For example, 1:3 (against, aka 3:1 in favor) odds would have a moneyline of -300, or winnings of 100 on a 300 dollar stake.

So we essentially have the same math as fractional odds, with two twists (rescale and different definitions pos/neg). For positive moneyline \(M_+\), we have directly \(w=M_+/100\). For negative moneyline \(M_-\), we have \(w=100/M_-\).

Using the relation \(p=1/(w+1)\), we find

\[p = \frac{1}{M_+/100 + 1} = \frac{100}{M_++100}, \quad\text{and}\quad p = \frac{1}{100/M_-+1} = \frac{M_-}{100+M_-}\]Comparison

As a tidy comparison, let’s look at a bunch of examples organized in a table:

| Probability (p) | Decimal Odds (D) | Fractional Odds (F) | Moneyline Odds (+) | Moneyline Odds (-) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1 | 10.00 | 9/1 | +900 | (-11) |

| 0.2 | 5.00 | 4/1 | +400 | (-25) |

| 0.3 | 3.33 | 7/3 | +233 | (-43) |

| 0.4 | 2.50 | 3/2 | +150 | (-67) |

| 0.5 | 2.00 | 1/1 | +100 | -100 |

| 0.6 | 1.67 | 4/6 | (+67) | -150 |

| 0.7 | 1.43 | 3/7 | (+43) | -233 |

| 0.8 | 1.25 | 1/4 | (+25) | -400 |

| 0.9 | 1.11 | 1/9 | (+11) | -900 |

Note the moneyline odds are the same at 50/50. Note also we don’t use moneyline (+) for \(p>=0.5\) and we don’t use (-) for \(p<=0.5\), so I put those in parentheses.

Getting the book involved

So far, there’s been an exact map between \(w\) (winnings), the odds, and the probability. That will always exist, but in practice the bookie will nudge the winnings up or down based on his guess of the true probability, so that he’s guaranteed to make some profit. Let’s see how this works.

Balancing the book

First of all, bookie’s need to have a balanced book – that is, payout for one bet offsets the loss from another. An easy way to do this is a heads-up game. Let’s say there’s a game between Team A and Team B, the bookie gives it a 50/50 shot, he offers even odds to Alice and Bob, who both pay him a dollar for the chance to win a dollar. The bookie’s okay: no matter who wins the game, he takes the one bettor’s bet to pay the other.

(Quick thought experiment without getting too far ahead of ourselves: what if more people want to play? So long as the bookie keeps the exact same number on each side of the bet, he’s okay. But he may need to adjust the offered odds to do this, to entice people toward the side he’s red on.)

Vig

But this is a lot of work and risk for the bookie, with no reward. So for a game with a true 50/50 shot, he’ll typically set something like a -110 moneyline (pay 110 to win 100). Now, he still uses the loser’s buy-in to pay the winner, but he only owes the winner 100: he keeps the other 10 for himself.

This fee (called the vigorish, or “vig”) is now baked into the odds. Before, the odds were a pure representation of the probability, now they are not. The juiced-up odds give an implied probability, but we are interested in the true probability. In our example, -110 odds imply a slightly more than 50\% shot (slight favorite) — but how can both teams have more than a 50% shot!?

Implied and true probability

In most situations we can back the vig out of the odds and find out what the bookmaker’s true probability is.

Let’s continue with this case of two teams playing each other. Again, say the moneyline for both teams is -110. We know this implies \(p=110/(110+100)=0.524\), but that’s for both teams which adds up to \(0.524\ast 2=1.0476\)! The chance of one of the teams winning should be 100%, not 104%. This reveals the vig of 0.0476, which on 210 dollars of winnings is \(210\ast 0.0476=10\). It also reveals the bookmaker’s true estimate of the probability for both teams as an even 50%.

More generally, let decimal odds for team 1 and 2 be \(D_1\) and \(D_2\), respectively. Since the probability of team \(k\) winning is \(p_k=1/D_k\), we should have \(1/D_1+1/D_2=1\). But in fact, we know the house takes a cut of \(V\), \(1/D_1 + 1/D_2 - V=1\), or \(V=1/D_1+1/D_2-1\). Let \(p_1'\) be the true probability of team 1 that we want — we can find it by normalizing by the total,

\[p_1' = \frac{1/D_1}{1/D_1 + 1/D_2} = \frac{1/D_1}{V+1}\]In our example earlier, this works out as \(.524/1.0476=0.5\).

We’ve been using decimal odds to keep the math clean but the same applies for the other expressions of odds — just replace the \(p_k=1/D_k\) with the equivalent for fractional, moneyline.

It’s good to get a feel for what the odds correspond to in the bookmaker’s true estimation. You know -110 isn’t really a favorite, it’s probably even odds. Looking at a matchup with +410 and -485 offered, you know that adds to 1.025 total probability, which implies a vig of 0.025, and so +410 isn’t a \(100/510=0.196\) underdog, it’s a \(0.196/1.025=0.192\) underdog. You’re paying for a stronger team than what’s really on the field.

Bet!

As a quick demonstration and a teaser for the next post, let’s simulate the things like EV and vig and implied probability that we’ve been discussing.

In theory, with any bet (favored or underdog), if there is no vig, we should break even, on average (EV=0). Let’s check that.

-

Note: Critically, notice we are setting the bookmaker’s offered bet on a probability which exactly captures the true game outcome — that is, we’ll have the bookmaker be a perfect oracle. This is not true in real life: only God knows the true probability, the casino just gets really close.

-

Note: First we’ll consider doing a one-off bet, many times, to directly simulate expected value. This is not real-life, doing a sequence of bets, with a bankroll. We’ll do that in the next post

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

np.random.seed(314) # for reproducibility

N = 1000000 # number of experiments

probs = np.arange(.1, .99, .1) # true probabilities to simulate

print('True prob Odds Avg win')

for prob in probs:

odds = 1 / prob # decimal odds (winnings + 1)

results = np.random.rand(N) # actual outcome

mask = results < prob # True if won, False if lost

win = np.where(mask, odds-1, -1) # net if won, -1 if lost

print(f' {prob:.2f} {odds:.2f} {np.mean(win):.4f}')

True prob Odds Avg win

0.10 10.00 -0.0026

0.20 5.00 -0.0019

0.30 3.33 0.0017

0.40 2.50 0.0014

0.50 2.00 -0.0001

0.60 1.67 0.0006

0.70 1.43 0.0006

0.80 1.25 0.0001

0.90 1.11 -0.0003

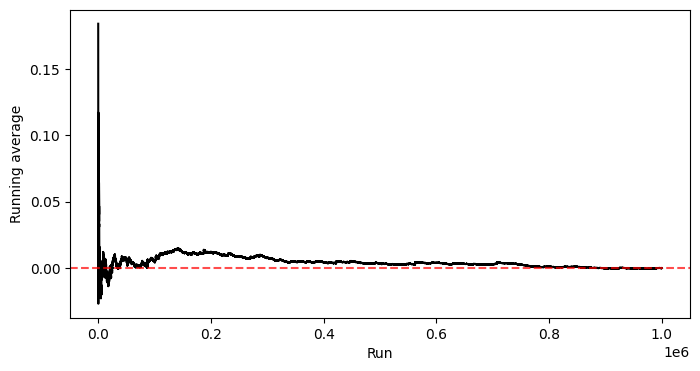

We can even make it “harder” (to converge). Let’s consider making one-off bets on random probabilities, instead of the same one 1M times. It’ll take longer to converge, but we’ll see the same trend.

np.random.seed(314)

N = 1000000 # number of experiments

probs = np.random.rand(N) # probability of Team 1 winning

odds = (1 / probs) # decimal odds (winnings + 1)

results = np.random.rand(N) # actual outcome

mask = results < probs # True if won, False if lost

win = np.where(mask, odds-1, -1) # net if won, -1 if lost

running_avg = np.cumsum(win) / np.arange(1, N+1)

running_avg = running_avg[100:] # drop "burn-in"

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1,1, figsize=(8, 4))

ax.plot(range(running_avg.shape[0]), running_avg, 'k-')

ax.axhline(y=0, color='r', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

ax.set_xlabel('Run')

ax.set_ylabel('Running average')

plt.show()

As expected, when we do a million one-off bets on Team 1, whether they are favored or underdog, and the outcome of the game is exactly aligned with the bookmaker’s odds, we break even.

It’s interesting how long this takes to converge — even after thousands of bets, we have no sense of what our average winnings might be.

Now consider some what-ifs: what if we include a vig? what happens if these bets are in sequence, not one-off? what if the bookie is not an oracle? what if we have access to a more accurate probability estimate than the bookie (i.e. we have an “edge”)?

We’ll answer the first two questions here, and save the latter two for a different post.

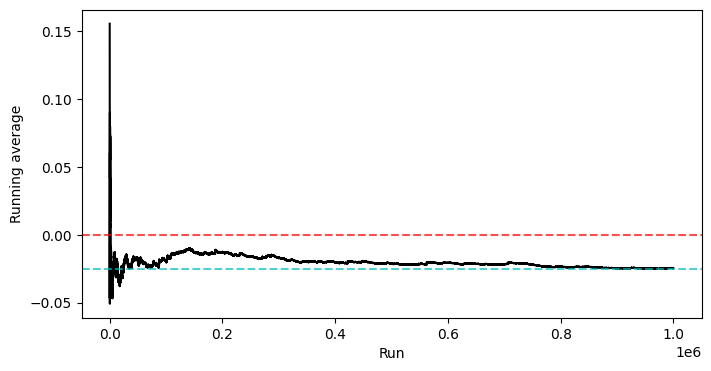

First, let’s include a vig. Let’s say the bookie always takes a vig of 2.5% (0.025). Recalling

\[p_1' = \frac{1/D_1}{V+1}\]we know that

\[D_1 = \frac{1}{p_1'(V+1)}\]So for example, if the true probability is 0.4, then the “fair” odds are \(1/0.4=2.5\), but the vig-adjusted odds should be \(1/(0.4*1.025)=2.439\).

np.random.seed(314)

N = 1000000 # number of experiments

probs = np.random.rand(N) # probability of Team 1 winning

vig = 0.025

odds = 1 / (probs*(vig+1)) # decimal odds (winnings + 1)

results = np.random.rand(N) # actual outcome

mask = results < probs # True if won, False if lost

win = np.where(mask, odds-1, -1) # net if won, -1 if lost

running_avg = np.cumsum(win) / np.arange(1, N+1)

running_avg = running_avg[100:] # drop "burn-in"

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1,1, figsize=(8, 4))

ax.plot(range(running_avg.shape[0]), running_avg, 'k-')

ax.axhline(y=0, color='r', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

ax.axhline(y=-1*vig, color='c', linestyle='--', alpha=0.7)

ax.set_xlabel('Run')

ax.set_ylabel('Running average')

plt.show()

Unsurprisingly, we see we’re no longer breaking even — we’re paying for a better team than is actually playing, so eventually we converge to an average of losing at the exact rate of the vig.

This still feels very artificial though, because it isn’t simulating our actual bankroll. If we make a series of these bets, what’s our wallet look like?? That’s what I’ll explore in the next post, this behavior over time, and the effect of different bet sizes.

Written on January 20th, 2025 by Steven Morse