Steven Morse personal website and research notes

Quarto, Part 1 (Theory)

Written on March 1st , 2017 by Steven MorseWhat is Quarto?

This post outlines some frivolous math things related to the game Quarto. My wife got me this game for Christmas, and kept beating me at it, so I decided to study the math and structure of the game in hopes of gaining an edge. She still beats me at it regularly, but the math is interesting.

(I plan on posting a “Part 2” with a Java and/or Python implementation of a simple playable AI for the game, based on some older work I have up on Github.)

Quarto is a 2-player game invented by Blaise Muller, a Swiss mathematician and game designer. It consists of a \(4\times 4\) board and 16 pieces. Each piece is a unique combination of four attributes:

- tall or short

- white or black

- circular or square

- solid or hollow.

For example, there is exactly one tall-white-circular-solid piece. The board begins empty. Players take turns placing one piece at a time onto the board.

Goal: The goal is to be the first to place four pieces in a row with at least one attribute in common. (Kind of like a very intense game of tic-tac-toe. Or Connect-4 for adults.)

The Twist. The twist is that you pick the piece that your opponent will play. For example, to start play, Annie selects a piece from the pile, hands it to Bob, and Bob plays that piece. Second turn: Bob selects a piece from the pile, hands it to Annie, who plays it. And so on. (As a result, each player makes two decisions each turn - where to play and what piece to pass.)

According to various sources, the game was solved in 1998 by Luc Goossens, and is a draw for both players assuming perfect play. I haven’t been able to find an archived copy of the paper.

Counting things

But let’s think about how big this game is — how many unique possible games are there? First let’s assume all pieces are the same, and we just care where the pieces are on the board. Second, let’s consider all 16 different types of pieces, and then try counting how many variations we have.

The Board

How many different combinations of the 16 spaces on the board are there, i.e. how many different choices of where to move are there? The obvious answer is \(2^{16}=65,536\), since there are 2 possible states for each square: a piece being there, or not.

But with board symmetries (rotations, flips), the answer is much less. For example, on the first move, placing a piece on any corner is the same essential move, same with the middle four spaces, same with the eight outer edge spaces. So there are really only 3 distinct first moves.

Similar cancellations occur on subsequent moves. Working it out by hand, we see there are 3 distinct first moves, 21 distinct second moves, … and after that the by-hand method gets a little tough.

Polya’s Enumeration Theorem

We can represent a board-state with the mapping \(f : X\rightarrow Y\), with \(X=\{1,2,...,16\}\) representing the spaces on the board, and \(Y=\{0,1\}\) representing whether there is a piece on that space (0 for no, 1 for yes). The space of all possible boards is \(F=\{f_i\}\), and \(\lvert F\rvert=2^{16}\).

Let \(S_F\) be the group of all permutations (the symmetric group) of \(F\) and \(G\in S_F\) be the group of rotations and reflections, i.e. the dihedral group.

Now let \(G\) act on \(F\). We notice that for some \(g\in G\), \(f_1 \ast g = f_2\). This represents a rotation or flip of the board. For some specific \(f\in F\), we define \(G_f = \{f\ast g \ \vert \ g\in G\}\), and say \(G_f\) is a \(G\)-orbit in \(F\). We notice each orbit represents a distinct state of the board as we observed before.

We would like to know the number of orbits in \(F\), that is the total number of distinct boardstates. We can think of this as \(\vert F/G\vert\) or sometimes denoted \(\vert Y^X / G\vert\).

Polya’s Enumeration Theorem provides a way to count this entity, i.e. count the number of orbits of a group action on a set. It states

\[\vert Y^X / G\vert = \frac{1}{\vert G\vert } \sum_{g\in G} \vert Y\vert ^{c(g)}\]where \(c(g)\) is the number of cycles in the permutation \(g\). If we think of a permutation as a universe of possibilities (i.e. the universe of single rotations from a given starting board), then the number \(c(g)\) represents the count of possibilities in this universe — the formula basically does the intuition we started with of counting \(2^{16}\) for the 16 possibilities in the non-symmetrical universe, and continues adding universes, then ``norming’’ by the number of universes available. Please continue to the next paragraph if this interpretation seems nonsensical.

We can easily verify the formula by hand for a \(2\times 2\) board (number distinct orbits \(=6\)), or even a \(3\times 3\) board (distinct orbits \(=102\)). Example: the distinct boardstates of a \(2\times 2\) board are:

x | x o | x o | x o | o o | o o | o

--|-- --|-- --|-- --|-- --|-- --|--

x | x x | x x | o x | x o | x o | o

But for our \(4\times 4\) case, we’ll rely on the formula.

Imagine transformations of the board as matrices, so for example the identity is:

\[e = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 2 & 3 & 4 \\ 5 & 6 & 7 & 8 \\ 9 & 10 & 11 & 12 \\ 13 & 14 & 15 & 16 \end{pmatrix}\]This permutation consists of some set of cycles. For the identity, it is a series of single cycles: \((1)(2)...(16)\). (1 goes to 1, 2 goes to 2, …). So \(c(e)=16\). But for example, a clockwise rotation is

\[r = \begin{pmatrix} 13 & 9 & 5 & 1 \\ 14 & 10 & 6 & 2 \\ 15 & 11 & 7 & 3 \\ 16 & 12 & 8 & 4 \end{pmatrix} = (1 \ 4 \ 16 \ 13)(2 \ 8 \ 15 \ 9)(3 \ 12 \ 14 \ 5)(6 \ 7 \ 11 \ 10)\]and so \(c(r)=4\).

The group of possible permutations is \(G=\{e, r, r^2, r^3, f, rf, r^2 f, r^3 f\}\), where \(r\) is a clockwise rotation and \(f\) is a flip, and note \(f^2=e\) and \(r^4=e\). Count up the number of cycles in each, and compute

\[\vert Y^X / G\vert = \frac{1}{8} \Big( 2^{16} + 2^4 + 2^8 + 2^4 + 2^8 + 2^6 + 2^8 + 2^6\Big) = 8,308\]the number of distinct boardstates.

So the formula is kind of saying: how many distinct board-states are there without regard to symmetry? \(2^{16}\). How many distinct single rotations can we do? \(2^4\). etc. etc. Sum these up and divide out by (“norm by”) the number of different symmetries we considered.

The Pieces

We run into equivalences when we’re counting how many different ways to play the pieces, too. For example, the Tall-White-Circle-soliD (TWCD) piece and the Tall-Black-sQuare-Hollow (TBQH) piece both have only one thing in common. Is there a difference between that pairing and, say, SWCD with SBQH? Or TWQD with SBCD? If we are only looking at a single pairing (and there are no others on the board), then those are all functionally equivalent.

The relationships between the pieces is all that matters. In fact, we might have two game-states with completely different pieces on the board, but if the relationships between the pieces are the same, the games are essentially the same. Like the board-states, it seems there are probably far fewer distinct piece-states than at first glance. However, we need some way to represent the structure of these relationships so we can build a permutation matrix G and count distinct states like with the board.

Notation. One thing is very natural: let’s represent each piece with a binary number from 0 to 15. Thus \(0 = 0000_b\) is SWCH, \(15 = 1111_b\) is TBQD, \(9=1001_b\) is TWCD, etc.

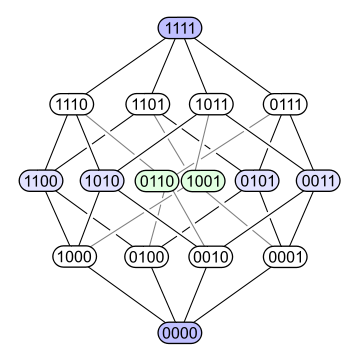

This notation exposes a relationship between pieces: each piece has exactly 4 pieces with 3 things in common with it, 6 pieces with 2 things in common, 4 pieces with 1 thing in common, and 1 piece with nothing in common, its opposite. For a piece \(p\), call these sets \(A_p\), \(B_p\), \(C_p\), and \(D_p\), respectively. For example (dropping the b-subscript):

\[\begin{align*} p &= 0000 \\ A_p &= \{0001, 0010, 0100, 1000\} \\ B_p &= \{0011, 0101, 0110, 1001, 1010, 1100 \} \\ C_p &= \{0111, 1011, 1101, 1110 \} \\ D_p &= \{1111\} \end{align*}\](Also note this 1-4-6-4-1 relationship is the 5th row of Pascal’s triangle.)

Mapping pieces to the board

Let’s start by just putting all the pieces on the board, and applying Polya’s enumeration theorem to count how many distinct ways there are to do this. Now we’ll have the rotation and flip symmetries as before, but also new symmetries we expect resulting from relationships between the pieces.

Define a function \(t \ : \ P\rightarrow X\) that maps the pieces \(P=\{0, 1, ..., 15\}\) to the board space \(X\). There are 16! \(\approx\) 20 trillion possible functions of \(t\), call this set \(T\).

We now need a symmetry group \(H\) to act on \(T\). First imagine the identity element in this group as a matrix

\[e = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 \\ 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 \\ 12 & 13 & 14 & 15 \end{pmatrix}\]Now let \(p=0000_b\), in the top left corner. Now we see its similarity sets occupy bands radiating away from it:

\[\begin{align*} A_0 &= \begin{pmatrix} 0 & \fbox{1} & \fbox{2} & 3 \\ \fbox{4} & 5 & 6 & 7 \\ \fbox{8} & 9 & 10 & 11 \\ 12 & 13 & 14 & 15 \end{pmatrix} \quad\quad B_0 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 & \fbox{3} \\ 4 & \fbox{5} & \fbox{6} & 7 \\ 8 & \fbox{9} & \fbox{10} & 11 \\ \fbox{12} & 13 & 14 & 15 \end{pmatrix} \\ C_0 &= \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & 5 & 6 & \fbox{7} \\ 8 & 9 & 10 & \fbox{11} \\ 12 & \fbox{13} & \fbox{14} & 15 \end{pmatrix} \quad\quad D_0 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 & 3 \\ 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 \\ 8 & 9 & 10 & 11 \\ 12 & 13 & 14 & \fbox{15} \end{pmatrix} \end{align*}\]Remarkably, if we rotate each quadrant of the matrix clockwise, the relationships stay in place. In this case we now have the matrix,

\[r = \begin{pmatrix} 4 & 0 & 6 & 2 \\ 5 & 1 & 7 & 3 \\ 12 & 8 & 14 & 10 \\ 13 & 9 & 15 & 11 \end{pmatrix}\]and we note for \(p=4\), \(A_p=\{0,5,6,12\}\), \(B_p=\{1,2,7,8,13,14\}\), etc.

There are many other symmetries. Call the quadrant rotation \(r\), with subsequent rotations \(r^2\), \(r^3\). We can also rotate the entire matrix, \(R\), or flip it, \(F\). We can also flip quadrants: switch the bottom and top halves of \(P\), call this \(f\). We can also swap rows: call this \(s\). Altogether, the symmetry set \(H\) for the matrix \(P\) consists of

\[H = \{e, r, r^2, r^3, f, rf, r^2 f, r^3 f, s, ..., F, ..., R, ... \}\]Example

Let’s take some arbitrary mapping \(t_1\in T\) and apply a permutation from \(H\).

\[t_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 13 & 9 & 2 & 3 \\ 0 & 11 & 14 & 5 \\ 7 & 1 & 15 & 8 \\ 4 & 10 & 6 & 12 \end{pmatrix}\]is our mapping, and consider the quadrant rotation \(r^3\), which is

\[r^3 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 5 & 3 & 7 \\ 0 & 4 & 2 & 6 \\ 9 & 13 & 11 & 15 \\ 8 & 12 & 10 & 14 \end{pmatrix} = (0 \ 4 \ 5 \ 1)(2 \ 6 \ 7 \ 3)(8 \ 12 \ 13 \ 9)(10 \ 14 \ 15 \ 11)\]which acts on \(t_1\) to produce

\[t_1 \ast r^3 = t_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 9 & 8 & 6 & 2 \\ 4 & 10 & 15 & 1 \\ 3 & 0 & 11 & 12 \\ 5 & 14 & 7 & 13 \end{pmatrix}\]which is also a mapping in \(T\) and which we now check is equivalent in essential board information to \(t_1\).

For example, pieces \(7=0111_b\) and \(14=1110_b\) in \(t_1\) correspond to pieces \(3=0011_b\) and \(15=1111_b\) in \(t_2\). Both pairings share exactly two attributes. Consider relationships between 3 pieces: pieces \(13=1101_b\), \(9=1001_b\), and \(2=0010_b\) in \(t_1\) correspond to pieces \(9=1001_b\), \(8=1000_b\), and \(6=0110_b\) in \(t_2\). We check all relationships are maintained: 13 and 9 share three attributes, as do 9 and 8 … 9 and 2 share one attribute, as do 8 and 6 … 13, 9, and 2 share no attributes together, neither do 9, 8 and 6. Etc.

Return to Polya

So we now have the problem in a form amenable to the orbit counting theorem from before, and can say

\[\vert X^P / H\vert = \frac{1}{\vert H\vert } \sum_{h\in H} \vert X\vert ^{c(h)}\]However we must remember this only accounts for piece symmetries, not board symmetries. A \(G\)-action on a board mapping may not correspond to an \(H\)-action on a piece mapping. For total, unique final board states including pieces and boards, we could do

\[\vert Y^X / G\vert \times \vert X^P / H\vert\]as an upper bound.

Another consideration is that we are only looking at endstates for pieces so far, i.e. with all pieces on the board. How many different ways are there to get to a given configuration? How many of those are permissible within the rules? How many of those are equivalent under symmetry?

We are only scratching the surface here, which is why I’d really like to get my hands on the paper by Luc Goosens since I assume he addresses some of these questions. Until then, however, let me point out an interesting observation.

Connection to the 4-cube

The permutation set \(H\) for the Quarto pieces is very interesting. Why is it when you take the matrix with the number 0 – 15 in order and rotated the quadrants, the matrix maintained certain relationship between the binary representations of those numbers?

We’d like to relate the space to some object, and then use a well known dihedral group to represent the symmetries. (Instead of using a clunky flat matrix.) A good analogy is to use a 4-cube, or tesseract, and think of the binary numbers as the coordinates of the vertices of the cube in 4-space. Then if you choose a vertex \(v\), \(A_v\) are the adjacent vertices, \(B_v\) are the vertices 2 steps away, \(C_v\) are the vertices 3 steps away, and \(D_v\) is the vertex on the opposite side of the 4-cube. Thus, \(H\) seems to be the dihedral group of a 4-cube.

Like all things, in hindsight, this is quite obvious. We have a 16-element set, and we are trying to identify symmetries. Of course this should correspond to the 16-element set called the coordinates of a 4-cube in Euclidean space! Of course!

Hopefully this has interested you as much as it has me, and best of luck if you ever play my wife.

Written on March 1st , 2017 by Steven Morse