Steven Morse personal website and research notes

1 - AI and Machine Learning: the big ideas

Series: A (Slightly) Technical Intro to AI

- AGI, Specialized AI, and Machine Learning: the big ideas

- Peeking under the hood with a linear model

- Expanding the framework: bigger data, bigger models

- Getting crazy: (Deep) neural networks

- A Safari Tour of Modern ML Models

- Ethics, Limitations, and the Future of AI

Artificial intelligence (AI) buzz is in crescendo, and for good reason. Watching a steering wheel move expertly even as your hands pull away is like being a child again, seeing the white rabbit emerge from the empty black hat. Many feel compelled to publicly pontificate on what else AI might conjure and the effects in their realms of expertise.

The problem is, although there are thousands of think-pieces on the high-level implications of AI in fields from healthcare to nuclear deterrence, and thousands of technical research articles on state-of-the-art innovations, there are extremely few resources in between. Occasionally an article will make a valiant attempt to explain some specific aspect of the actual mathematics in layman’s terms, but the language and mathematics is left very broad and the linkage remains muddy.

In this series I’ll try to bridge a bit of this gap between hype and understanding.

This article is written for anyone who is interested in AI research, has no technical training in the subject, but has some latent aptitude or fondness for technical details — perhaps a STEM undergraduate degree, or an MBA, or even just a love for puzzles and a fondly remembered high school algebra teacher — and would like to know a little more about what’s going inside the magician’s hat of contemporary AI.

Generalized vs. Specialized AI

Let’s get something straight

We have to be honest about what AI is before understanding how it works. The computer engineering used to create modern specialized AI like autonomous vehicles and digital assistants is as distant from the technology required to produce the generalized AI of our Westworld and Skynet fantasies as the Apollo mission’s technology was from sending a manned mission to Alpha Centauri.

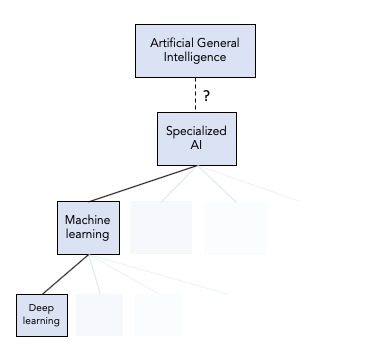

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) — or you may hear “strong AI” — refers to … well, no one can decide how exactly to define it, but it means (perhaps) a machine that can think and learn and act like a human, maybe even attain consciousness (whatever that might mean).

Do we have any way to measure a computer’s intelligence? Can a machine think? Is this meaningful to ask? After all, we are comfortable saying machines can fly (a drone), but we wouldn’t say machines can swim, even though autonomous boats exist — is this all just a semantic riddle?

In answer to the question “can machines think,” the computing visionary Alan Turing posed what he called an “imitation game”, more commonly known as the Turing Test, which basically asks whether a human can interact with the machine and tell whether it’s human or not, for example through conversation. This test has retained a grip on AGI research’s imagination for decades, although it certainly has weaknesses: for example, it is behavioral, focused on inputs and outputs, and is this enough to determine whether it is truly thinking? This is the crux of the argument behind famous thought experiments like the Chinese room.

AGI is a deep topic at the intersection of philosophy, mathematics, computer science, logic, neuroscience, and it has captivated some of the greatest minds of the last century. Perhaps, as some say, the singularity is near. But it is certainly well beyond the scope of this humble blog post and, most likely, well beyond what the human race is capable of achieving in the near future.

But funny enough — AGI is not what’s making headlines.

Specialized AI

Specialized, or “weak,” or “narrow” AI, is in the news and revolutionizing the world, but it is not really intelligence at all. It is specific mathematical models finely tuned to solve specific practical problems. In this series we will examine what some of the common models are and how one “tunes” them, but we will find it feels a lot less like interacting with The Singularity and more like fitting a curve to data. Any impression such a model gives of emergent agency is, mathematically speaking, completely illusory.

Nevertheless, specialized AI is extremely powerful, and it’s the focus of this series. We’ll start by understanding the big idea behind the currently most successful type of specialized AI called machine learning (ML), then peek under the hood of an actual ML model, then show how to expand this framework to the deep learning models (and others) making headlines. We’ll close with some caveats about ML’s practical and ethical challenges, and survey the current wisdom on the future of AI.

A quick history of specialized AI

Not so long ago …

Humans were fantasizing about creating autonomous, human-like machines far before the modern era — the ancient Greek myth of Talos was essentially a giant robot, and even fiction like Frankenstein points to the same dream of bringing the inanimate to life that powers the modern AI movement.

Yet although ideas of “counting machines” and “programmable computers” date back well before the 20th century to big names like Liebniz and Babbage and Lovelace, “AI” as a discipline began around the 1950s in parallel with the birth of modern computing. At a Dartmouth workshop in 1956, several of the big names in early AI met, considered a pivotal moment for the field (they coined the term “artificial intelligence” at this workshop, by the way).

From the ’50s on, AI research proceeded in fits and starts: booms of innovation, punctuated by short periods of frustration (“AI winters”). AI conquered problem after problem — acting as convincing chatbots (ELIZA), accomplishing simple physical tasks in “micro-worlds”, controlling robots and self-driving cars, acting as “expert systems,” defeating grandmasters at chess (Deep Blue) — and this was all well before even the 2000s.

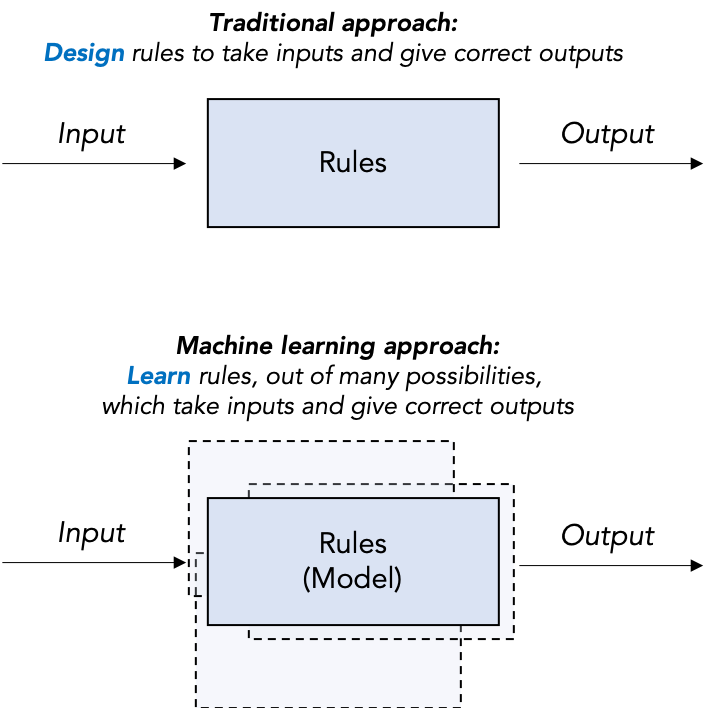

The focus of AI research for most of this history was on very top-down approaches: humans designed rules, or logic, or expert systems, which they then programmed a computer to understand and implement. However, AI research shifted focus sometime in the ’90s to a more bottom-up approach: let the computer learn the rules itself by placing it in an environment and training it how to behave. This is, broadly speaking, the idea behind machine learning and the powerful subset of methods called deep learning.

Learning the Rules

Take a moment to really ponder how something like a self-driving car actually works. Is it a series of pre-programmed rules? “At a stop sign, come to a complete stop and check for other vehicles, then proceed.” But how would its video sensor recognize what’s a stop sign, or other vehicles? Maybe more rules: if is a red octagonal shape nearby, this is a stop sign. But how do we account for different sizes and orientations of the sign, or a red cardinal perched on the sign? And we still must reckon with things like predicting the motion of nearby vehicles in order to make braking decisions, location tracking, following posted speed limits; the list is seemingly endless.

As you wrestle with this thought experiment, you should quickly realize that having a human — even a team of humans — attempt to write down a list of rules to govern a car’s behavior would never be sufficient for a task this complex. And although many autonomous systems can be built up from simple pre-programmed rules — e.g. a thermostat, a Roomba — perhaps unsurprisingly, this is not at all how modern AI works.

Modern (specialized) AI flips this approach on its head: instead of designing rules to take inputs and give good outputs, it uses inputs and corresponding outputs to learn a set of rules, called a model. We want the machine to learn the rules by itself, based on data, thus why we dub this approach machine learning (ML). Don’t be fooled: the essential idea of ML is not new, and many methods now labeled machine learning are just applied statistical techniques that are decades, or even hundreds of years, old. But the recent availability of enormous amounts of data, powerful computers, and ground-breaking theoretical innovations have led to its current role as the face of AI.

As another example, contrast the AI behind IBM’s Deep Blue that defeated Garry Kasparov at chess in 1997 with the AI behind AlphaGo that defeated Lee Sedol at Go in 2015. Deep Blue was based on a brute-force search of possible moves from each board position (the “minimax” algorithm), with a human-designed built-in heuristic to help eliminate obviously unfruitful possibilities (“alpha-beta pruning”). This is a completely top-down, human-designed algorithm. AlphaGo, while employing some tree search like Deep Blue, was based on a reinforcement learning scheme that learned a policy for play based on extensive observation (“training”) with expert human games. We’ll examine this ML model in greater detail in Part 5.

Interestingly, while ML dominates the current AI scene — in particular the brand of ML called deep learning which we discuss in Part 4 — due to its ability to accomplish specialized tasks, it is very much an open question whether it even has the potential to achieve generalized AI.

Regardless, the remainder of this article will deal with ML, from its simplest form to its more bleeding-edge incarnations, because these are the systems that are behind nearly all “AI” headlines. To recap, here’s a partial and oversimplified taxonomy of terms we’ve mentioned so far:

Machine Learning, a 10,000 ft view

The big idea …

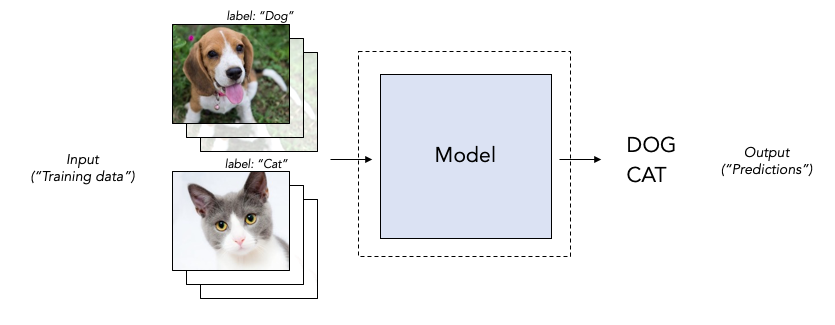

One may envision most machine learning solutions as a black box that receives an input and gives an output.

For example, let’s say we wanted to “train an AI” to correctly label images of dogs and cats. Our “AI” needs to be some magical black box, or function, or model that reads in an input image of either a dog or a cat, and spits out a label of “dog” or “cat” that is (hopefully) correct.

Once we select a model to use (call this Step 0), there are two steps going on here:

- Train the model to give correct outputs as often as possible.

- Predict outputs accurately, given new, previously unseen inputs.

Feel free to anthropomorphize this process and imagine a toddler: you sit him in your lap, open a book, and as you point to pictures of dogs you say “dog,” to pictures of cats, you say “cat.” You have him repeat the correct label back to you and correct his errors. After some time you point to a new picture of a cat or dog — one he has never seen before! — and expect him to say the correct label.

His model was selected in utero as a network of brain synapses (Step 0), your supervised reading to him was that model’s training (Step 1), and the new picture quiz was the prediction (Step 2).

I have a couple small, noisy neural networks in my home that I co-authored with my wife, and watching them learn like this is a bit magical, really. What’s almost as magical to me is that we can train a machine to do this exact (specialized) task, and do it just as well or better.

Before we move on, please note there are lots of wrinkles and caveats to these steps — for example, we haven’t specified what “often as possible” or “accurate” mean, we seem to be excluding the class of models that learn without supervision, we’re not necessarily always concerned with prediction, it’s common to do parts of different steps in a non-sequential order, etc. etc. — but for now let’s follow the broad brushstrokes.

… and the big problem

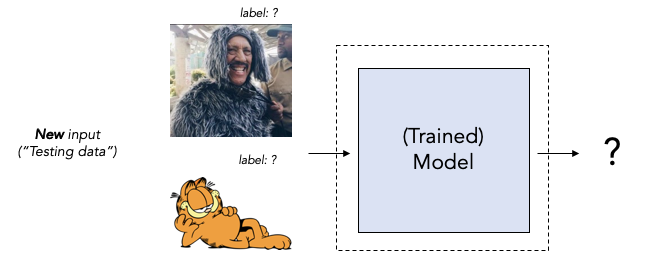

Once we have a trained model, we are ready to deal with new, never-before-seen inputs, the all-important Step 2: accurately predict.

This is called “out of sample performance” or the ability of the model to “generalize.” Returning to our toddler, if he learned what a dog is from books, will he recognize one on the street? Will he recognize a terrier if all he’s seen is dachsunds? What about someone in a dog costume? With a child, we unthinkingly assume he will have no trouble with these generalizations. A lot of the AI buzz comes from certain models’ almost human-like ability to generalize to new data.

Now let’s explore — in some gentle mathematical detail — the workings of an actual model. On to Part 2!

- AGI, Specialized AI, and Machine Learning: the big ideas

- Peeking under the hood with a linear model

- Expanding the framework: bigger data, bigger models

- Getting crazy: (Deep) neural networks

- A Safari Tour of Modern ML Models

- Ethics, Limitations, and the Future of AI