Steven Morse personal website and research notes

6 - Ethics, Limitations, and the Future of AI

Series: A (Slightly) Technical Intro to AI

- AGI, Specialized AI, and Machine Learning: the big ideas

- Peeking under the hood with a linear model

- Expanding the framework: bigger data, bigger models

- Getting crazy: (Deep) neural networks

- A Safari Tour of Modern ML Models

- Ethics, Limitations, and the Future of AI

Ethics

Applying machine learning methods to a problem brings with it new, and sometimes unexpected, ethical challenges. As we know now, ML models are fit to data — and therefore, in some way, models reflect their data’s ethics and assumptions. For example, if we feed data about crimes committed exclusively by Hispanics into a crime prediction model, we should not be surprised if our model has a bias (in both the usual sense of the word, and the specific statistical sense) toward predicting Hispanic crime.

In 2018, Amazon “scrapped a secret AI recruiting tool” that showed bias against women. We now know the “secret AI” was likely some sort of regression-based model, developed based on historical hiring data within the company, and was no doubt biased due to changes in hiring practices and the prevalence of males in the early days of Amazon, and therefore the training data. A lot closer to negligence than nefariousness, knowing what we know now about how ML models work — but if left unchecked, a source of hidden and systemic prejudice in the company’s hiring process.

Another trend is development of machine learning algorithms to use facial images to predict things like criminal behavior, or intelligence, or sexual orientation. This sort of research immediately raises red flags: first, for the purpose of such an invasive tool, and second, for its likely built-in prejudices based on its training data. Models exhibiting this sort of modern phrenology typically just reflect their training data. In a study claiming to predict criminal behavior based on a facial image, the non-criminal images were personal headshots, while the criminal images were taken post-conviction. Unsurprisingly, the model’s archetype of a criminal face was frowning.

Machine learning ain’t perfect y’all

Complicating matters further, we often don’t fully understand how machine learning models work. As we mentioned during the section on deep learning, unlike a linear model with two easily interpretable parameters of slope and intercept, modern ML models have millions of parameters which interact in truly incomprehensible ways. As a result, models can trick us, have unexpected failures, and fail to generalize in the way we think they will.

Models are sneaky. We construct ML models, roughly speaking, by ruthlessly minimizing some error function. So we should not be surprised that often, they find creative ways to optimize themselves within our imposed constraints but circumventing our intent. And because they are so inscrutable, often this “cheating” goes undetected.

For example, Facebook chatbots designed to automate parts of Facebook’s Marketplace began communicating with each other in a made-up language that was unintelligible to humans. An image-to-image GAN was discovered to be hiding data in the encoded images in order to improve its performance.

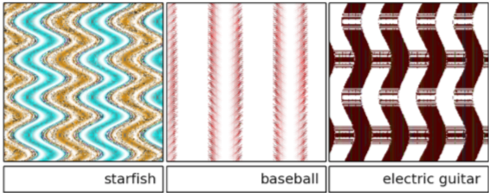

Unexpected failures. Also because their inner workings are often not fully understood, ML models can have unexpected failures. Uber, Tesla, Google and other companies at the forefront of self-driving cars continue to wrestle with cars having fatal collisions due to unexpected failures in their internal model of surroundings. Microsoft famously had to shutdown its Twitter chatbot, Tay, that was trained on Twitter data to interact with humans, when within hours of launch it began tweeting racist epithets. A common problem with even state-of-the-art image recognition models is their ability to be completely fooled by certain unexpected patterns — the images below were classified with 99% accuracy by a large CNN.

Remember, it’s specialized. These models are specialized for a specific task. We will run into problems when we try to have them pivot. You may remember IBM Watson’s impressive Jeopardy performance where it beat Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. IBM tried to repurpose Watson as an expert medical system, but it has so far been a little underwhelming.

You can take Lee Sedol and ask him to quit Go and become a professional Blackjack gambler, and we can safely assume he would be able to sit down at a table, with zero training, quickly grasp the relevant concepts, and do fairly well. But if you take AlphaGo, the algorithm that defeated him at Go, and try to input a hand of blackjack, it wouldn’t even understand the question.

What do the haters say

After reading this series, you should have a more tempered (but still excited!) outlook on the future of AI. For example, in these Atlantic articles, Henry Kissinger and others speculate about the destabilizing potential of AI on things like nuclear deterrence. Mr. Kissinger appears profoundly moved by the admittedly magical performance of models like AlphaZero, and can’t help but worry that a nuclear power may learn deterrence-beating strategies from an AI in the same way Go grandmasters now study AlphaZero’s otherworldly gameplay. But AlphaZero has fit its internal model to a contest with fixed rules, where two players make known moves on a finite board –– the nuclear “game” has no such traits, and like so many complex systems, defies over-simplification.

For this reason, many downplay the breathtaking advances of modern ML by pointing out that, in essence, it’s just curve fitting. As we have now seen, there is truth to this jab: all the models we’ve discussed have had a spirit connection to the simple linear regression model with which we began, despite their galaxy-level sophistication and jaw-dropping results.

One of these haters, the Turing Prize winner and AI visionary Judea Pearl, claims the future of AI depends on teaching machines the idea of causality (“the flooding caused the dam to break”), and with it ideas like agency (“the temperature rose because I raised the thermostat”) and counterfactuals (“I wouldn’t have gotten wet if I had brought an umbrella”). He points out that, despite our deepest wishes and the popular wisdom of today, this sort of knowledge is not self-evident in a dataset, and moreover requires new mathematics and revolutionary new ways of thinking.

He is not alone in being skeptical of the promise of deep learning, and it is a heated, ongoing debate. The counterpoint is simple enough: it now seems more likely than not that, when we do achieve AGI, it will contain a deep neural network.

Now that you’ve read all this math stuff … what do you think?

Parting thoughts

I’d like to offer two parting thoughts.

-

My intent for writing this series was to bridge the divide between the high-level commentary on AI you see in the news, and the deeply technical AI research going on in the field. I hope I found the right middle ground, and I hope that you now feel like a more intelligent consumer of (and participant in) the ongoing discussion about AI. If you’re on either side of this divide, whether an ML/AI expert or a casual reader, and see that I’ve missed something, please reach out.

-

Now that I’ve whet your palette, you may be wondering how to go deeper into the technical details of AI, specifically ML. I have a few suggestions. ML is equal parts math and computer science, so you should get your hands dirty in both as often as possible. To build programming and data science chops, I recommend finding a data-oriented topic that fascinates you (perhaps sports, or social networks, or finance) and find data in that topic, for example on a site like Kaggle that not only hosts the datasets, but has community-contributed code sandboxes. Building math chops is a little harder, and is going to require subjects like probability, multivariable calculus, and linear algebra. But don’t stress — this can, quite frankly, come second to a tinkerer’s appreciation of and knack with data and models. Once your hobby project has the hooks in, I recommend texts or courses that teach the math and code together, like the excellent Introduction to Statistical Learning by the authors of the more advanced canon, Elements of Statistical Learning.

Lastly, I hope you’ve learned something from this series, I certainly enjoyed writing it, and thank you for reading.

- AGI, Specialized AI, and Machine Learning: the big ideas

- Peeking under the hood with a linear model

- Expanding the framework: bigger data, bigger models

- Getting crazy: (Deep) neural networks

- A Safari Tour of Modern ML Models

- Ethics, Limitations, and the Future of AI